Question 2: why do we do statistics?

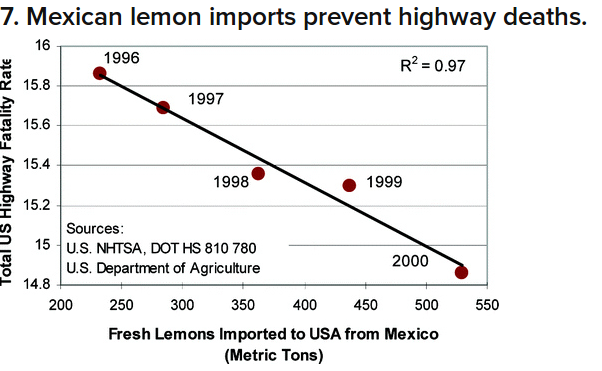

Association DOES NOT Imply Causation:

Recall: My Favorite Example.

Question: Why does association not imply causation?

Answer: Because more often than not there's some other explanation!

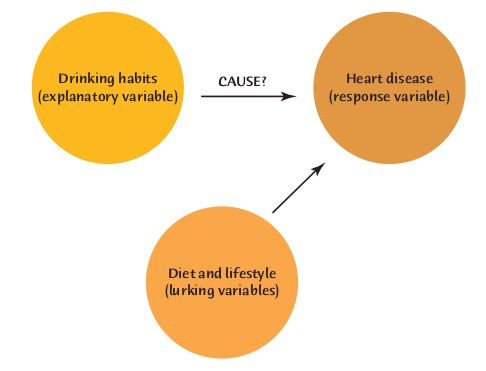

Vocab: A lurking variable is a variable that is not included as an explanatory or response variable in the analysis but can affect the interpretation of relationships between variables.

A lurking variable can falsely identify a strong relationship between variables or it can hide the true relationship.

Example: Many observational studies show that people who drink a moderate amount of alcohol have less heart disease than people who drink no alcohol or who drink heavily.

When we simply observe people’s drinking choices, the effect of moderate drinking is confounded with (mixed up with) the characteristics of people who choose to drink in moderation.

BIG Question: How do we establish causation?

Answer: We perform an experiment.

Vocab

An observational study observes and records data about from a sample of the population.

An experiment imposes a treatment on individuals in different groups and records their responses.

Example: Observational or Experiment?

Cell phones and brain cancer. A study of cell phones and the risk of brain cancer looked at a group of 469 people who have brain cancer. The investigators matched each cancer patient with a person of the same sex, age, and race who did not have brain cancer, then asked about use of cell phones. Result: “Our data suggest that use of handheld cellular telephones is not associated with risk of brain cancer.” Is this an observational study or an experiment? Why? What are the explanatory and response variables?

Example: Observational or Experiment?

The font matters! In general, high perceived effort is an impediment to changes in behavior, whether it is modifying your diet or adopting an exercise routine. Researchers divide 40 students into two groups of 20. The first group reads instructions for an exercise program printed in an easy-to-read font (Arial, 12 point), and the second group reads identical instructions in a difficult-to-read font (Brush, 12 point). They estimated how many minutes the program would take (open-ended) and used a 7-point rating scale to report whether they were likely to make the exercise program part of their daily routine (7 = very likely). As hypothesized by the researchers, those reading about the exercise program in the more difficult-to-read font estimated that it would take longer and were less likely to make the exercise program part of their regular routine. Is this an experiment? Why or why not? What are the explanatory and response variables?

More EXPERIMENT Vocab: In an experiment...

The individuals are called subjects.

The explanatory variables are called factors.

A treatment is something we do to the subjects.

If an experiment has more than one factor, a treatment is a combination of specific values of each factor.

How To Experiment Badly: Let subjects choose the treatment.

If our goal is to establish cause and effect, can you think of any problems with this?

Example: An Uncontrolled Experiment.

A college regularly offers a review course to prepare candidates for the Graduate Management Admission Test (GMAT), which is required by most graduate business schools. This year, it offers only an online version of the course. The average GMAT score of students in the online course is 10% higher than the longtime average for those who took the classroom review course. Is the online course more effective?

This experiment has a very simple design. A group of subjects (the students) were exposed to a treatment (the online course), and the outcome (GMAT scores) was observed.

Question: Can we conclude that online courses are more effective?

Answer:

Explanation of Grumpy Cat's Answer:

A closer look reveals that both groups differ significantly from one another:

The students who took the online course were older and more gainfully employed.

Grumpy Cat Conclusion: It's impossible to tell whether or not the inherent differences between groups, or the course itself, is responsible for the elevated scores.

BIG Question: How do we overcome the problem posed by the above example?

Drumroll please...

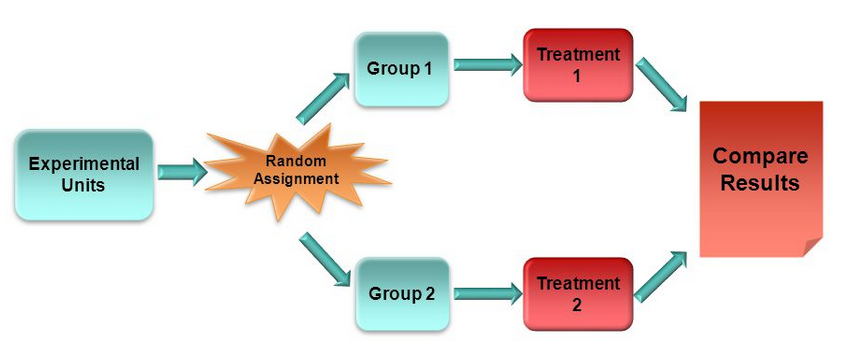

Randomized Comparative Experiment:

An experiment that uses both comparison of two or more treatments and random assignment of subjects to treatments is a randomized comparative experiment.

The Reasoning of Experiments

When we randomly assign subjects to treatments, we control for the effects of lurking variables.

The big idea is that we want the only difference between each group is the treatment.

The Basics of Experimental Design

The basic principles of statistical design of experiments are

- Control the effects of lurking variables on the response, most simply by comparing two or more treatments.

- Randomize—use chance to assign subjects to treatments.

- Use enough subjects in each group to reduce chance variation in the results.

Very. Very. Very. VERY! Important Vocab: Statistical Significance

An observed effect so large that it would rarely occur by chance is called statistically significant.

Some Considerations

If we want to separate cause and effect, we have seen that the only difference between groups must be the treatments themselves.

Again, like so many things in life, this isn't always easy to do in practice.

Example: Suppose you want to measure the effect of a medication.

The simple act of doing something which which is only believed to have some effect can have a positive outcome.

This is called the placebo effect.

This effect underscores the need for very careful consideration in isolating the effectiveness of a treatment.

Another BIG Question: How do we treat all subjects identically?

Answer: a double-blind experiment.

In a double-blind experiment, neither the subject nor the person administrating a treatment knows which treatment is being administered.

This is how most pharmaceutical companies test the effectiveness of their products.

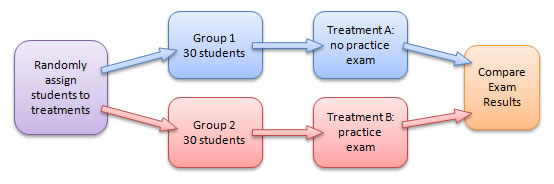

Another Common Design: Matched Pairs.

A matched pairs design compares just two treatments.

Choose pairs of subjects that are as closely matched as possible. Use chance to decide which subject in a pair gets the first treatment.

The other subject in that pair gets the other treatment.

The random assignment of subjects to treatments is done within each matched pair, not for all subjects at once.

Example: To Measure the effect of taking a practice exam versus not taking a practice exam to gauge the effect on the results of the real exam, match pairs students of students who are similar and randomly assign one from each pair to a treatment: practice exam/no practice exam.

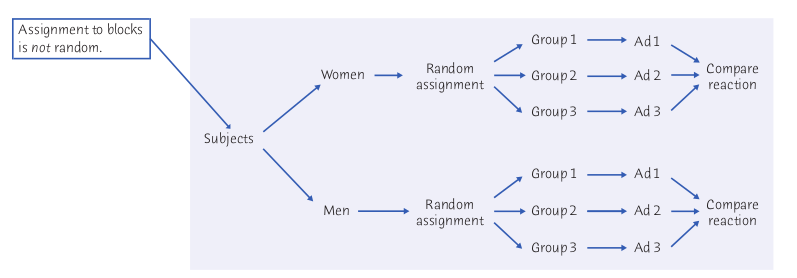

Another Common Design: Block Designs

Some subjects fall naturally into groups which aren't random.

Examples: Age Category, Sex, Lifestyle.

If we are interested in how treatments affect these groups separately, we have what is called a block design.

Example: Women and men respond differently to advertising. An experiment to compare the effectiveness of three advertisements for the same product will want to look separately at the reactions of men and women, as well as assess the overall response to the ads.