A Fundamental Question: What is statistics?

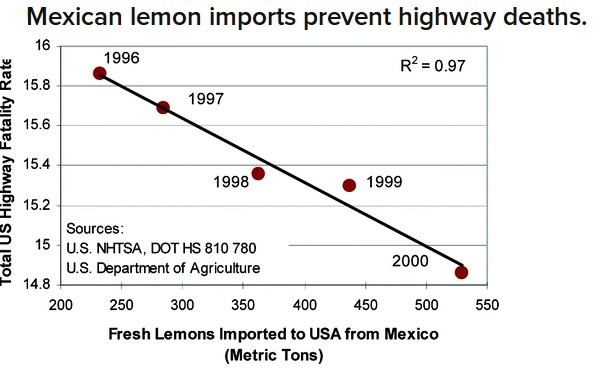

Big Fact: Association DOES NOT Imply Causation

My Favorite Example

Question: Why does association not imply causation?

Answer: Because more often than not there's some other explanation!

Vocab

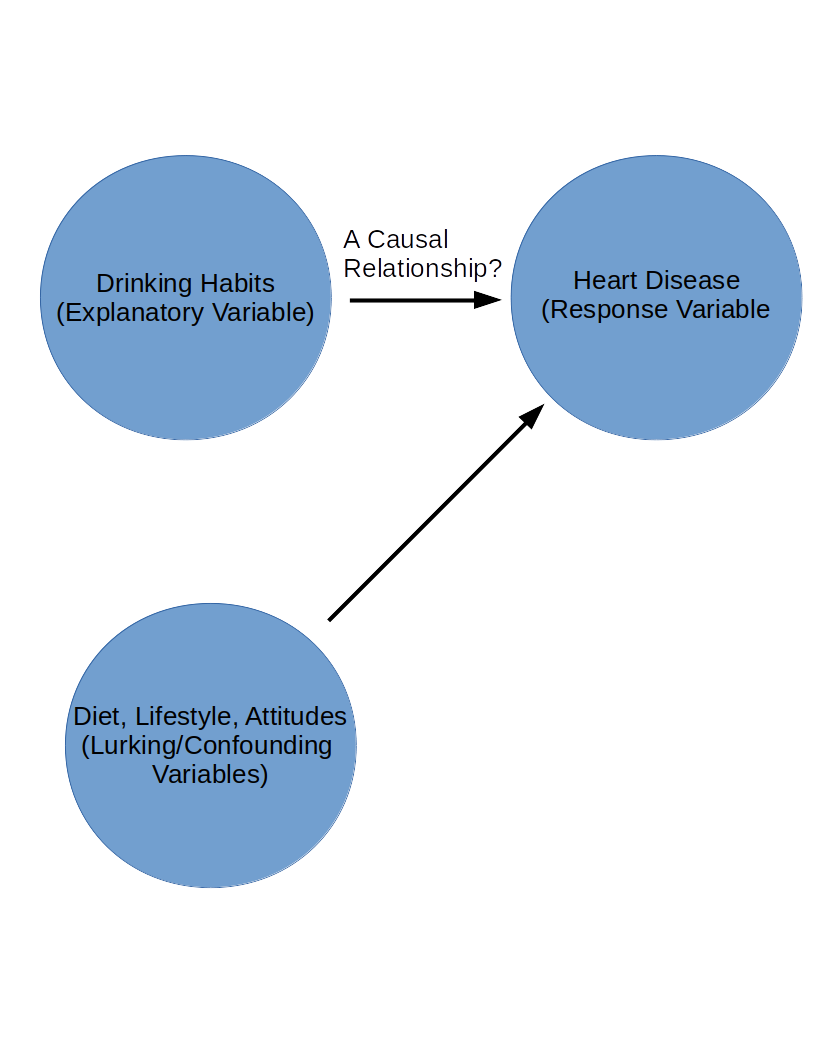

A lurking variable is a variable that is not included as an explanatory or response variable in the analysis but can affect the interpretation of relationships between variables.

A lurking variable can falsely identify a strong relationship between variables or it can hide the true relationship.

Example

There are lots of observational studies which conclude that people who drink a moderately have lower rates of heart disease than people who drink heavily or abstain completely.

Can we conclude that moderate drinking lowers rates of heart disease?

Answer:

By simply observing the drinking habits of participants, it is easy to confound moderate drinking with other habits of people who drink moderately.

Do people who drink moderately tend to make make better lifestyle choices such as diet, exercise, and other considerations? Do these other characteristics lead to better outcomes, or is it the moderate drinking? It's impossible to tell. The other characteristics which could explain lower rates of heart disease are lurking variables.

BIG Question: How do we establish causation?

Answer: We perform an experiment.

Vocab

An observational study observes and records data about from a sample of the population.

An experiment imposes a treatment on individuals in different groups and records their responses.

Example: Observational Study or Experiment?

A group of researchers want to understand if there is a relationship between weather and a person's mood.

On $30$ randomly chosen days of the year, researchers conducted telephone interviews asking participants to rate their mood without any mention of the weather in their area.

Participants rated their mood on a scale of $1$ to $5$ with $5$ being "excellent" and $1$ being "poor."

Researchers found that that colder, rainier weather is associated with lower mood scores.

Is this an observational study or an experiment? What are the explanatory and response variables?

Example: Observational Study or Experiment?

Suppose researchers divide participants into two groups:

One group is given instructions for a task which is printed in a font which is easy to read.

The other group is given the same instructions for the same task, but the instructions are written in a font which is difficult to read.

Both groups were asked to rate how difficult they believe the task to be.

It turns out that the group who read the instructions written in a difficult to read font perceived the task to be more difficult than the other group.

Is this an observational study or an experiment? What are the explanatory and response variables?

More EXPERIMENT Vocab: In an experiment...

The individuals are called subjects.

The explanatory variables are called factors.

A treatment is something we do to the subjects.

If an experiment has more than one factor, a treatment is a combination of specific values of each factor.

How To Experiment Badly: Let subjects choose the treatment.

If our goal is to establish cause and effect, can you think of any problems with this?

BIG Question: If we are trying to establish a causal relationship between two variables, how do we overcome the problems posed by the above examples?

Drumroll please...

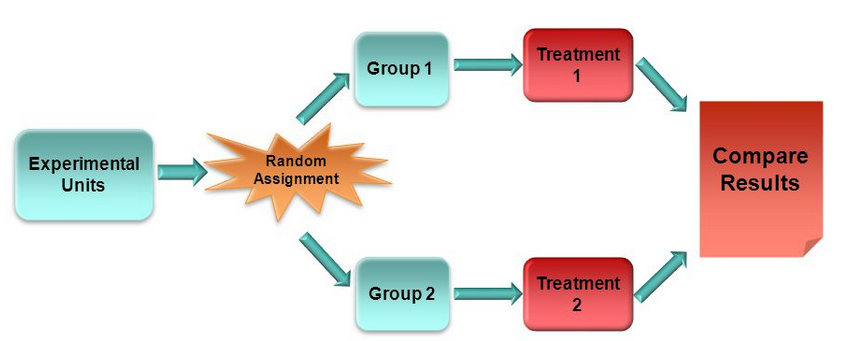

Randomized Comparative Experiment

An experiment that uses both comparison of two or more treatments and random assignment of subjects to treatments is a randomized comparative experiment.

The Reasoning of Experiments

When we randomly assign subjects to treatments, we control for the effects of lurking variables.

The big idea is that we want the only difference between each group is the treatment.

A group which is randomly assigned to receive the "do-nothing" treatment is called the control group.

Example

A group of agricultural researchers want to know what combination of fertilization and plant type have the best yield in a kind of corn. To answer this question, they perform an experiment which compared two factors: the nitrogen level in the soil to plant type.

One plant type is a normal variety and the other is a genetically-modified variation of the same variety.

The levels nitrogen fertilizer considered were $\mbox{0 kg/ha},$ $\mbox{50 kg/ha},$ and $\mbox{100 kg/ha}.$

Individuals of each plant type were randomly assigned to the six possible treatments. $$ \begin{array}{c|cc} \mbox{} & \mbox{Normal} & \mbox{GMO} \\ \hline \mbox{0 kg/ha} & \mbox{Group 1} & \mbox{Group 4} \\ \mbox{50 kg/ha} & \mbox{Group 2} & \mbox{Group 5} \\ \mbox{100 kg/ha} & \mbox{Group 3} & \mbox{Group 6} \\ \end{array} $$ The response variable is the yield and will be compared across treatments.

Very. Very. Very. VERY! Important Vocab: Statistical Significance

An observed effect so large that it would rarely occur by chance is called statistically significant.

We will talk more about statistical significance later in the course.

Some Considerations

If we want to separate cause and effect, we have seen that the only difference between groups must be the treatments themselves.

Again, like so many things in life, this isn't always easy to do in practice.

Example: Suppose you want to measure the effect of a medication.

The simple act of doing something which is only believed to have some effect can have a positive outcome.

This is called the placebo effect.

This effect underscores the need for very careful consideration in isolating the effectiveness of a treatment.

To control for the placebo effect, individuals are assigned a "placebo" treatment which has no effect.

For example, this might take the form of a sugar pill in place of an active medication.

The group which is randomly assigned a placebo treatment is often referred to as either the placebo group, or the control group.

Another BIG Question: How do we treat all subjects identically?

Answer: A double-blind experiment.

In a double-blind experiment, neither the subject nor the person administrating a treatment knows which treatment is being administered.

Double-Blind experiments are the clinical gold standard of whether or not a treatment has an effect.

This is how most pharmaceutical companies test the effectiveness of their products.

Fact of Life #1: Getting good data is HARD!

Before Collecting Data: Plan your study well. No amount of analysis can compensate for bad data.

Make sure you can answer the following questions (which is neither a definitive nor exhaustive list, but a good start):

- What do you want to know?

- Can you define your population?

- Can you reasonably take a random sample from this population?

- What are you going to measure?

- How are you going to measure it?

- Can you measure it?

Fact of Life #2: Getting good data might be ethically questionable.

Case Study: The Stanford Prison Guard Experiment

Case Study: The Milgram Experiment

Ethically Challenging Subjects: Humans

When trying to get information about human populations, please remember:

- don't hurt them (neither physically nor psychologically)

- be sure they know what they're getting into (informed consent)

Ethical Oversight: Institutional Review Board (IRB)

Fact of Life #3: Getting bad data is EEEEEEEEEEEAAAAAAAASY!

Ethics: While Collecting Data.

It may be a temptation to cut corners in gathering data.

For example, you may not want to visit a randomly chosen house because it's in a bad neighborhood.

Perhaps, after a long day you might even be tempted to fill in some numbers that "sound right" and call it good.

Dire Warning #1: Giving in to such temptations will ruin your study and your credibility.

Ethics: After Collecting Data.

Be Honest: Be sure to give your readers as much detail as possible about your sampling design, analysis, and any assumptions you made either in data collection or your analysis.

Avoid misleading analyses. This is a topic in and of itself which we will discuss more of later.

Dire Warning #2: If you're ever caught fibbing (either faking data, or not being completely honest about how you collected your data), no one will ever listen to you again. Your credibility will have been lost forever.

Ethics: After Collecting Data.

Any Result is a Revelation: Not finding an effect is neither good nor bad. It's only a conclusion.

It's Okay to Not Know: There's nothing wrong with asking someone for help. Most researchers find themselves in a position where they must seek advice from someone with expertise in another field.

DON'T DO IT!!! D: